Arthur Lismer, Igonish Dock, Cape Breton

Arthur Lismer, Igonish Dock, Cape Breton(December 27)

Comments on books I've read, illustrated.

Arthur Lismer, Igonish Dock, Cape Breton

Arthur Lismer, Igonish Dock, Cape Breton(December 27)

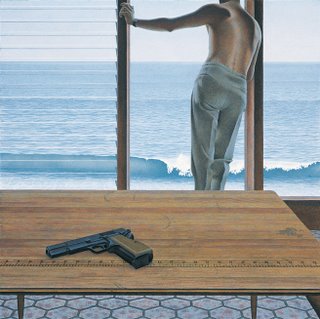

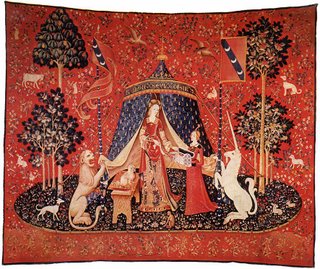

Heather Cooper, from Carnaval Perpetuel??

Heather Cooper, from Carnaval Perpetuel??(December 26) Loved it.

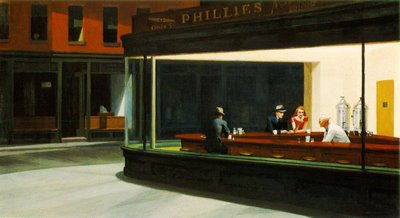

I cannot encapsulate Bel Canto better than the New York magazine reviewer who called it a “dreamlike fable in which the impulses toward beauty and love are shown to be as irrepressible as the instincts for violence and destruction.”

Sesheps, The Great Sphinx of Giza

Sesheps, The Great Sphinx of Giza Thomas Bewick, The Wolf Trap

Thomas Bewick, The Wolf Trap Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party

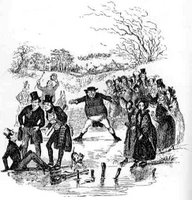

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party(October 26) I really liked Three Men in a Boat – it’s the buddy movie of its day – the Seinfeld or Mary Tyler Moore Show of the 1880s. It’s very funny. The story is nominally about one trip up the Thames in a rowboat undertaken by three young urban professionals, but this particular trip is really just the backdrop for a series of comic monologues about other boat trips and adventures and about life in general, à la George Carlin or Dave Barry. As the friends get ready for the excursion, for example, J., the narrator, pauses to lampoon weather forecasting and barometers: Then there are those new style of barometers, the long straight ones. I never can make head or tail of those. There is one side for 10 a.m. yesterday, and one side for 10 a.m. to-day; but you can't always get there as early as ten, you know. It rises or falls for rain and fine, with much or less wind, and one end is "Nly" and the other "Ely" (what's Ely got to do with it?), and if you tap it, it doesn't tell you anything. And you've got to correct it to sea-level, and reduce it to Fahrenheit, and even then I don't know the answer. The book is fun also because of the sensation of travelling back in time 120 years – paid work is done by children, people move their bathtubs around, a complete supper can be bacon and a jam tart, young men share single beds matter-of-factly. Spookily at one point, J. reverses the time-travel effect by making fun of the fashion of collecting antique china: Will the prized treasures of to-day always be the cheap trifles of the day before? Will rows of our willow-pattern dinner-plates be ranged above the chimneypieces of the great in the years 2000 and odd? Well, yes, they will! It was surprising that interspersed among the funny anecdotes and clever observations are serious little flights of poetic fancy that occasionally verge on the mawkish. I was struck by this one, though: And yet it seems so full of comfort and of strength, the night. In its great presence, our small sorrows creep away, ashamed. The day has been so full of fret and care, and our hearts have been so full of evil and of bitter thoughts, and the world has seemed so hard and wrong to us. Then Night, like some great loving mother, gently lays her hand upon our fevered head, and turns our little tear-stained faces up to hers, and smiles; and, though she does not speak, we know what she would say, and lay our hot flushed cheek against her bosom, and the pain is gone.

In the last month I've started six books and finished none: Six Easy Pieces (Richard Feynman), The Pickwick Papers (Charles Dickens), Cosmos and Psyche (Richard Tarnas), The Kite Runner (Khaled Hosseini), The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (Michael Chabon) and Collapse (Jared Diamond).

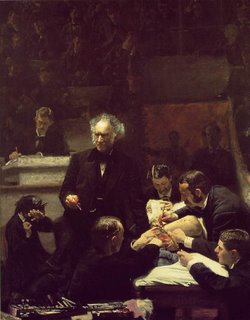

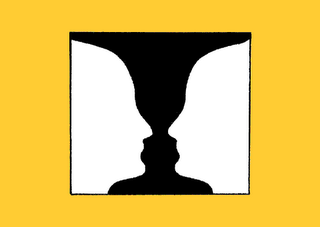

(May 15) Fun. I have gotten on a kick of watching What Not to Wear on Friday nights while wrestling the dog, and have slowly learned there’s a science to choosing clothes. Dress Your Best is mostly images with magazine-style cutlines and bullet points, not a book, really, but it gave me an awareness of the visual aesthetic of clothing that reminded me of learning the compositional aesthetic of The Oath of the Horatii in art history (only quicker).

Now, would Stacy and Clinton say that Madame X is dressed appropriately? Oh, I think so.

(May 7, 2006) Good read. I really liked it. I haven’t read a lot of time-travel novels (just the Diana Gabaldon books), but I feel like I know the genre from movies (Groundhog Day, Time Bandits, Austin Powers, Back to the Future, Lola Rennt, Peggy Sue Got Married, Somewhere in Time, Terminator, Prisoner of Azkaban) and TV (Quantum Leap, Mr. Peabody, Star Trek, Twilight Zone, Outer Limits), and I think that this was a very innovative approach to time-travelling. I like how she schemed it all out, so that for a while Henry knows more than Clare, then Clare knows more than Henry, and at almost every encounter one of them is surprised and one of them knows what’s going on. Despite this constant dislocation, both always know some of the “back story” and can guide the other through. The characters are very likable, and they do the harmless things you’d do if you had this kind of relationship with time -- they get a lottery win, they play the stock market, they get prepared for September 11th. It’s clever and imaginative. It gets a bit gruesome at the end, but Niffenegger must have felt that she couldn’t wind up the whole thing too happily.

(May 30) Hmm. I got this out of the library because I liked Gilead so much and because several reviews of Gilead harked back reverently to the predecessor, Housekeeping, as an amazing book. My expectations were very high, and they were not met at all, at all, at all. This is one of those books in which semi-insane people float around lyrically, occasionally noticing details of their environments. Because what they do is so aimless, it’s hard to bond with such characters. I don’t find myself looking forward to “what will happen next” -- it could be anything (shrug)

Charming, involving, but peculiar. I was a bit surprised by what this turned out to be. When it was mentioned in Gilead, it sounded like it might be about two men, one older, vying for the love of a young woman. That premise would have had some bearing on the love relationship and the conflict in Gilead if it were entirely the case. But, really, The Trail of the Lonesome Pine is a twist on the Pygmalion story, with the Eliza Doolittle character symbolizing Kentucky’s pre-industrial wilderness paradise. The age difference between the principal characters is completely different from that in Gilead: it’s slightly disturbing that Jack Hale falls in love with June at her young age. On the other hand, it strikes me as something you’d get away with in 1908, as well as with the usual anachronisms, such as the old-fashioned terms and turns of phrase and the unenlightened attitudes about class and race.

It’s quirky because it’s from 1908, but the author’s also quirky. The pacing is very uneven -- you can tell that Fox wove a fictional narrative around scenes he actually witnessed among mountain people -- he dwells on some moments with a vividness that is out of all proportion to their importance in the story while paying bare lip-service to moments that should be dramatic in the alleged story. He also has an odd way with a phrase every once in a while: he’ll write a sentence backward: “The longest of her life was that day to June,” or he’ll open a chapter in a funny, detached way: “Spring was coming: and, meanwhile, that late autumn and short winter, things went merrily on at the gap in some ways, and in some ways -- not,” or he’ll describe something bizarrely: “The Hoosier was delirious over his troubles and straightway closed his plant.” He shifts point of view frequently and without warning.

Still, I liked it a lot; I even ordered a fairy stone from www.highhopes.com.

Very interesting. Stout defines “conscience” convincingly as attachment to other people, or, basically, the ability to love and be loved. She then offers evidence that 4 per cent of the population are born without the ability to love or be attached, and they are our sociopaths, carrying out agendas that range from the relatively harmless to the unspeakably criminal, all under the impression that everyone is like them. If she is correct, there is no point feeling sorry for serial killers, rapists, child abusers, etc., or trying to rehabilitate or psychoanalyze them -- it’s not that they come from unhappy backgrounds that they are the way they are: they simply think that people with consciences are chumps.